Consumers are increasingly interested in knowing the origin of the food they consume. Pig rearing conditions related to animal welfare are issues of concern to the general population. In addition, the constant technification of pig production systems generates a great pressure between countries that must be more competitive every day in order to maintain international […]

Consumers are increasingly interested in knowing the origin of the food they consume. Pig rearing conditions related to animal welfare are issues of concern to the general population.

In addition, the constant technification of pig production systems generates a great pressure between countries that must be more competitive every day in order to maintain international trade.

Because of this, more emphasis is placed on seeking production techniques that meet these demands daily, especially thinking about reducing stress in each of the stages of the production cycle.

Stress and meat quality

One of the most stressful moments for the animal is the one originated during the pre-factory transport, which can trigger alterations in productivity, as it is the case of pale, soft and exudative (PSE) meats. Pre-slaughter handling practices will affect stress levels and therefore the occurrence of meat quality alterations.

PSE meats are produced when acute stress is generated prior to slaughter. Pigs that are genetically sensitive to stress (halothane gene) are more likely to suffer this type of alteration, but it can occur independently of genetics (Kerth, 2013, Chapter 7).

Acute stress generates an acceleration of glycolysis. Immediately post mortem, the metabolism is anaerobic and lactic acid is produced. The low pH, due to lactic acid, added to a still high beef temperature results in a protein denaturation of the meat.

It is due to this process that PSE meats have a low water holding capacity (WHC) (Adzitey & Nurul, 2011; Offer, 1991; Offer & Knight, 1988). To detect PSE meats, the pH should be measured 30 minutes after slaughter, considering as possible indicators values lower than 6.1 Josell, Martinsson, Bogaard, Andersen, and Tornberg (2000).

In countries where the incidence of this alteration is greater, pH values equal to or less than 5.9 are taken as a reference (Van de Perre, Ceustermans, et al.,2010, Van de Perre, Permentier, et al.,2010 and Adzitey and Nurul, 2011).

Factors such as genetics; season; handling of pigs prior to slaughter, during loading, transport and unloading; as well as handling practices and type of housing of pigs, will directly affect stress conditions and therefore, the quality of meat obtained (Brown, Knowles, Wilkins, Chadd, & Warriss, 2005; Van de Perre, Ceustermans, et al., 2010; Van de Perre, Permentier, et al., 2010).

This article will mention considerations that should be taken into account to reduce the stress generated due to the factors discussed above.

Pre-slaughter handling: practices prior to transport

Fasting

Pigs must have access to water while waiting for loading. In addition, it is recommended that they fast (only on food), the duration of which will depend on the distance they have to travel to the slaughterhouse.

A minimum fasting time of 5 hours could be considered for journeys of more than 8 hours, while for journeys of less than 8 hours, a minimum fasting of 10-12 hours prior to transport could be appropriate, taking a maximum fasting time of 24 hours between loading and slaughter.

Loading duration

The duration of the loading should be as short as possible to limit stress on the pigs. It is recommended that it does not exceed 30 minutes between the first pig and the last pig on the truck.

Lighting

An adequate light source must be present in the loading area and in the truck compartment. In addition, it must be operational for the entire duration of the loading process with the engine off.

The direction of the light, when loading and unloading, should be from behind the animals to the front.

Pre-slaughter handling: loading and unloading

Calm pre-slaughter handling that conforms to the animals’ natural behaviour speeds up loading operations, improves animal welfare and reduces economic losses due to injuries and bruises.

Another aspect to consider is that pigs have a wide angle of vision and can see everything around them. However, they have a blind spot located just behind the animal. If a person stands in that spot, the animal may become nervous because it cannot see what is happening. Handlers should always avoid being in the blind spot when approaching a pig.

Pigs should be allowed to move towards the loading ramp at their normal walking speed. Faster walking will cause loss of balance, slipping and falling. Any distractions in the path such as chains, plastic, cloth or any moving object should be moved out of the way to avoid creating fear.

Also, noise should be limited to a minimum level, so shouting during loading should be avoided.

Under no circumstances should electric prods be used to move animals.

Pre-slaughter handling: transport

The longer the journey, the greater the risk that well-being will be adversely affected. There are 4 main aspects in animal transport, which have an impact on welfare as the length of the journey does. These are: physiological state of the animal, food and drink, rest and thermal environment.

Pre-slaughter handling Animals transported on long journeys may suffer prolonged exposure to extreme heat or cold, as well as radical changes in climate that can increase the stress of transport.

During the journey the driver must remain alert to anything that may be wrong, inspecting the livestock when required and taking action if a problem arises that affects the animals.

To do this, it is preferable to make frequent inspection stops during the trip, especially on long journeys.

The wind chill of the truck can be assessed by looking for signs of panting among the animals (indicates that the temperature is too high). This can also be observed in case of overloading of animals or poor ventilation in the truck. The huddling of the pigs indicates that they are cold.

Water is needed to prevent dehydration and weight loss in the truck during long journeys. Pigs should not be fed during the trip to avoid dizziness and vomiting.

Animal Density

A density of 0.4 to 0.5 m2 /100 kg live weight generates higher PHs compared to those obtained with higher or lower densities and reduces the possibility of death during transport.

Higher densities may cause an increase in fights between pigs and lower densities are related to falls inside the truck. These conditions alter animal welfare and therefore increase the risk of producing PSE meat.

Loading and unloading facilities

Another point to consider is the loading and unloading ramps.

Check before (un)loading the maintenance of the loading bay and waiting pens (doors, light, ventilation, cleanliness and quality of the floor) to limit the risk of pigs falling, tripping or being injured.

Poor loading and unloading facility designs increase the risk of slips, falls, bruises and injuries and additional stress to the animals, resulting in poor quality meat and economic losses.

Ramp design should facilitate loading and unloading with minimal problems for the animals and bruising.

These ramps will increase the heart rate of the pigs, the more pronounced the ramp, the more the heart rate of the animals will increase. Therefore, it is recommended that they have a maximum angle of 20°.

As for the corridors, ideally, they should not have right angles as they generate nervousness and fear in the animal. Curved walkways will improve the movement of the pigs since they avoid the visualization of obstacles in the way.

In addition, there should be no gaps between the truck loading system and the farm loading platform or dock, as this increases the risk of injury and fractures. It is of great importance that the floor is not made of slippery material.

Unloading

During the unloading of the pigs in the slaughter plant the quantity and intensity of the animals’ vocalizations increase markedly. The pigs’ vocalisations activate their defence mechanisms and are therefore considered to be indicators of stress.

Unloading areas should be safe and have a wide, clear and straight path from the vehicle to the waiting pens and there should be enough personnel to unload the pigs as soon as the truck arrives.

During unloading, pigs should be closely observed for their general condition and signs of suffering and/or deteriorating health.

Animal observations to be considered include: apathy, glassy eyes, fever, rapid breathing rate, abnormal postures, immobility, skin discolouration, fatigue, resistance to movement and difficulty in maintaining balance.

References

Pre-slaughter handling and pork quality. L.Vermeulen, Van de Perre, L. Permentier, S.De Bie, G.Verbeke, R.Geers. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meatsci.2014.09.148

Good Practice Guide for the Transport of Pigs. European Union, 2013. doi: 10.2875/706309

Subscribe now to the technical pig magazine

AUTHORS

Bifet Gracia Farm & Nedap – Automated feeding in swine nurseries

The importance of Water on pig farms

Fernando Laguna Arán

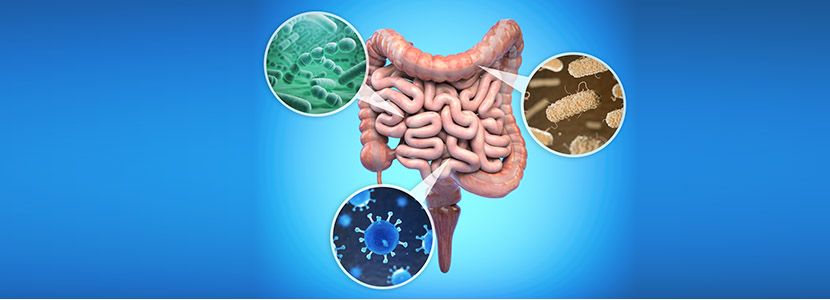

Microbiota & Intestinal Barrier Integrity – Keys to Piglet Health

Alberto Morillo Alujas

Impact of Reducing Antibiotic use, the Dutch experience

Ron Bergevoet

The keys to successful Lactation in hyperprolific sows

Mercedes Sebastián Lafuente

Addressing the challenge of Management in Transition

Víctor Fernández Segundo

Dealing with the rise of Swine Dysentery

Roberto M. C. Guedes

Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae – What are we dealing with?

Marcelo Gottschalk

The new era of Animal Welfare in Pig Production – Are we ready?

Antonio Velarde

Gut health in piglets – What can we do to measure and improve it?

Alberto Morillo Alujas

Interview with Cristina Massot – Animal Health in Europe after April 2021

Cristina Massot

Differential diagnosis of respiratory processes in pigs

Desirée Martín Jurado Gema Chacón Pérez